One of the definitions given by the Cambridge Dictionary for the word “freedom” is “the state of not being in prison”. However, its primary meaning is “the condition or right of being able or allowed to do, say, think, etc. whatever you want to, without being controlled or limited.” Considering these two definitions in tandem raises an intriguing question: what if someone’s freedom is more restricted in the outside world and they feel more free in prison? Does this make the concept of freedom subjective? Also, how long can a person remain silent before retaliating as their freedom is increasingly restricted? In such a scenario, will the retaliation be peaceful or violent? Cinematographer-turned-director Venu’s psychological political drama Munnariyippu (Warning), starring Mammootty, explores these questions and dissects the psyche and life of a middle-aged man, CK Raghavan, stuck in such a quagmire.

“Living in constant fear is very dull. It will destroy our freedom. Whether a man or a woman, no one should allow that to happen. Freedom depends on our definition of it. My perception of freedom might be different from yours. We may have to weed out certain obstacles that stand in our way. Isn’t that what freedom is? When it occurs at home, it’s domestic violence; when it happens in society, it’s revolution. Be it in Cuba or at home, blood will spill during revolutions,” a drunk Raghavan tells a bunch of strangers in a bar.

When he was finally granted freedom after spending five decades in prison, Brooks Hatlen (James Whitmore) in director Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption (1994) couldn’t hold it together for long. “In here, he’s an important, educated man. Outside, he’s nothing,” says Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding (Morgan Freeman), explaining how prison has institutionalised Brooks. For Brooks, prison was more than just a place of confinement — it was the only space where he felt a true sense of belonging.

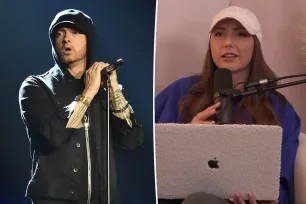

We first see Raghavan as he stands quietly in the office of jail superintendent Rama Moorthy (Nedumudi Venu) who is explaining to freelance journalist Anjali Arakkal (Aparna Gopinath), hired to ghostwrite his service story, a rehabilitation scheme he developed for prisoners released after long sentences. Convicted of double homicide — his wife and a Marwadi girl living at his employer’s home — Raghavan, however, becomes visibly disturbed when someone refers to him as a murderer. “I haven’t killed anyone,” he tells Anjali when Moorthy steps out for a moment.

Just before this moment, we are shown a scene featuring a party hosted by senior journalist KK (Prathap Pothan) for aspiring scribes. There, he declares German novelist Franz Kafka as one of his favourite writers, with Josef K as his favourite Kafka character. Josef K is the protagonist of Kafka’s novel The Trial, which begins with the line, “Someone must have been telling tales about Josef K, for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.” It’s no coincidence that Venu and screenwriter Unni R placed these two scenes in tandem, especially since Munnariyippu, which released 10 years ago, is rich with metaphors, analogies, similes and imagery.

Watch Munnariyippu trailer here:

In his cell, Raghavan has pinned two photos on the wall — of the two people he’s accused of killing. “No one has ever come to visit him, nor has he ever applied for parole,” a cop tells Anjali, further piquing her curiosity. “These walls are funny. First, you hate them; then you get used to them; enough time passes, you get so you depend on them,” Redding says about Brooks. After her first conversation with Raghavan, Anjali begins to feel the same about him too. Despite having served 20 years in jail — six years beyond his actual sentence — Raghavan speaks with a surprising calmness and that too in allegories and nearly everything he says has multiple layers of meaning.

Although Raghavan has no evidence to prove his innocence, he is unwavering in his belief that he is not guilty. The intellectual depth in the things he wrote down in his diary captures Anjali’s interest even more, leading her to publish his story in a prominent news magazine. When the article gains popularity, she is offered the chance to turn it into a book. However, the unexpected fame that follows disrupts Raghavan’s life in prison, leading to his release and effectively ending his extended stay there. This part of Munnariyippu also critiques how quite a few journalists focus solely on producing “interesting” stories that will bring them fame, without considering the impact it can have on the person(s) featured/discussed in their work.

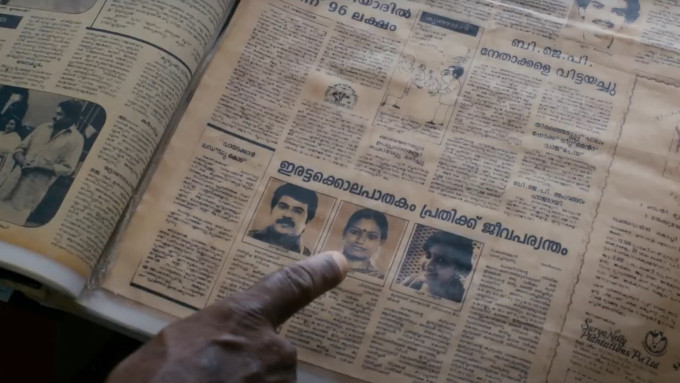

Newspaper clipping reporting that CK Raghavan has been sentenced to life imprisonment for double homicide. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Newspaper clipping reporting that CK Raghavan has been sentenced to life imprisonment for double homicide. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Even before his release, Anjali starts acting as if she owns him, forbidding him from meeting a journalist from Delhi. At the same time, she gives him (false) hope by promising to be there for him after his release, just to manipulate him into writing for her.

While Anjali resides in a plush apartment, she arranges for Raghavan to stay in a cramped single room in an old building, located far from the main areas of the city. Reaching the place requires navigating through a couple of narrow alleys and climbing a precarious staircase. To Raghavan, the room seems to be “well-equipped,” as it includes a bed, a table, a chair, a table lamp and a wastebasket. When he mentions this to Anjali, she shamelessly says, “How could you be given a room without these facilities?” Yet, a quick look around makes it clear that the room is only a bit better than his prison cell, reflecting how she seeks to exploit him, believing that an ex-convict deserves no more than the bare minimum.

Mammootty and Aparna Gopinath in Munnariyippu. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Mammootty and Aparna Gopinath in Munnariyippu. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Although she is a writer herself, Anjali tells Raghavan they can easily meet the deadline since he “has no other job and just needs to sit and write,” as if it were a mechanical task. However, when Raghavan realises he has to write his own life story, his demeanour and body language shift, showing signs of tension and unease. Anjali, however, either doesn’t notice this change or simply doesn’t care.

Whenever she leaves, Anjali instructs Raghavan to close the door, confining him to the room, where he’s expected to do something against his will. In jail, he feels merely confined, with no expectation to engage in anything he doesn’t want to. In contrast, here he feels isolated, with no one to even talk to. Even KP Anil Kumar (Minon), the young boy from the hotel who brings his food, is always busy. Here, Venu, who also handled Munnariyippu’s cinematography, frequently frames Raghavan through the bars of his window, symbolising the jail he’s in.

Raghavan in his cramped single room in an old building. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Raghavan in his cramped single room in an old building. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Anjali’s treatment of Raghavan becomes even more evident during her meeting with the senior management of the publishing house. When the boss advises her to ensure no one has access to Raghavan, Anjali confidently replies, “I am pretty certain no one can. He’s safe in my custody.”

However, her plans start to backfire as Raghavan repeatedly fails to begin writing, coming up with a new excuse each time. Though she tries to persuade him, he continues to fail. When Anjali realises he isn’t writing, her attitude toward him changes. She tries to even emotionally manipulate him, expressing disappointment that he isn’t trying. At the same time, she also begins to treat him with indifference, as he is unable to produce the service/product she forced upon him. Even the way she enters his room changes; she now opens the door with a bang.

One day, when Anjali visits Raghavan’s room and finds him missing, she becomes agitated and irritated, thinking it unacceptable for him to focus on anything other than writing for her. This reaction highlights her elitist, feudalistic and authoritarian attitude.

Venu also doesn’t forget to offer more on Raghavan’s character beyond his interactions with Anjali. During their outing, it’s revealed that Raghavan has no money and only Anil does, ironically. Raghavan is also shown becoming visibly tense upon encountering an elderly, seemingly Marwari, couple who might be connected to the girl he is accused of murdering.

Anjali’s plans start to backfire as Raghavan repeatedly fails to begin writing, coming up with a new excuse each time. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Anjali’s plans start to backfire as Raghavan repeatedly fails to begin writing, coming up with a new excuse each time. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

The movie also critiques the field of journalism and in one scene, KK is seen lecturing Anjali about professional ethics immediately after having made a misogynistic comment on female journalists, which clearly highlights a typical old-school, elitist media giant mentality.

Munnariyippu adds a political and economic dimension too to its narrative when Chacko (Prithviraj Sukumaran) comes to meet Anjali as a prospective groom. Interestingly, Chacko works in, of all the places in the world, the US, known for its capitalist economy and supremacist tendencies of a huge population. Anjali quickly agrees to marry him and it’s later mentioned in passing that she will move to the US after marriage. Intriguing, isn’t it?

Aparna Gopinath as freelance journalist Anjali Arakkal in Munnariyippu. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Aparna Gopinath as freelance journalist Anjali Arakkal in Munnariyippu. (Image: Silly Monks Mollywood/YT)

Anjali’s treatment of Raghavan becomes increasingly disrespectful and she even suggests that she is doing him a favour by providing him with the room and covering his expenses. After the Delhi journalist tracks Raghavan down and meets him, Anjali moves him to an even more dilapidated house, farther away, with no other houses nearby. At this point, Raghavan’s demeanour starts to change. As Anjali leaves him at the new location, he smirks oddly. Later, he is shown taking a walk outside, picking up an iron rod, examining it and then throwing it away.

On the final day of their contract, realising she cannot meet the deadline or make Raghavan write, Anjali comes to meet him and there, mocks him and the diary entries that initially attracted her. But he doesn’t respond and continues to just look at her, smiling, and that too an eerie smile with a shade of determination. He hands her a set of papers with his writings and as she reads, he begins packing his stuff.

As she reads his account, Anjali grows increasingly frightened, understanding the true nature of the person she has been dealing with and why he says, “I haven’t killed anyone,” and that it’s not because he hasn’t committed a crime, but because he doesn’t see himself as guilty. “You asked me where I want to go now. I’ve decided. I am returning to jail,” Raghavan says with a sinister smile before striking Anjali on the head with the iron rod. Unsettingly, he wears the same red-checkered shirt he wore on the day of his release here too. The next scene shows him sleeping peacefully in his cell, now with three photos on the wall: his wife, the girl and Anjali. Fascinatingly, in Munnariyippu, there is no crime or punishment — only freedom and the consequences of depriving someone of it.

Significantly before Munnariyippu delves into the core of its plot, Venu masterfully encapsulates the film’s theme with a striking shot featuring a quote by renowned poet and novelist Sylvia Plath: “I desire the things which will destroy me in the end,” reflecting how Anjali’s desire to get Raghavan to pour his life into words and thereby gain fame, ultimately leads to her tragic demise.

Mammootty’s outstanding performance, which subtly but effectively reveals the complex layers and nuances of Raghavan, including the shades of grey in him, is definitely a major reason Munnariyippu remains memorable even after a decade. At the same time, Munnariyippu‘s enduring impact is also due to the themes it explores and the way Venu and Unni conceived and portrayed these vast topics in a minimalistic manner. Bijibal’s music and Beena Paul’s editing too are equally brilliant.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.