A wickedly deceptive film that aims to subvert every theme it tackles — gender, caste, the conventions of horror cinema — director Rahul Sadasivan’s Bramayugam is perhaps the most nihilistic Indian movie in years. Even Sandeep Reddy Vanga, determined as he often is to be the edgiest person in the room, would shudder at the thought of presenting a world this bleak — although, incidentally, at least one subplot in Bramayugam is very similar to the central revenge story in Animal.

The rest of it, believe it or not, takes the standard issue uprising template that is so popular in South Indian films, and refashions it into something that A24 would happily acquire and market to within an inch of its life. Brayamayugam stars Mammootty — the Malayalam cinema icon who is currently in a zone that only Denzel Washington has existed in before him — as a man who appears to be rotting in real-time. This man is Kodumon Potti, introduced to us as an upper-caste landowner in 17th Century Kerala, but later revealed to be a shapeshifting ‘goblin’ in human form.

Also read – Kaathal – The Core: Jeo Baby must kill his inner crowd-pleaser; it’s the only thing separating his films from true greatness

Kodumon lives by himself in a crumbling old mansion in the middle of a forest, although he has an Igor-like servant to do his bidding. This man, whose responsibilities include cooking for his ‘master’ and also disposing of dead bodies on his behalf, expels spittle and snark in equal measure. One day, a mysterious stranger named Thevan shows up at their doorstep, starving for food and desperate to outrun the slave traders that he has just escaped from. Thevan is taken aback at Kodumon’s generosity, which he views as genuine, but we, the viewers, immediately recognise as performative. He is offered a meal and lodging, despite having alerted Kodumon to the fact that he belongs to a lower caste. The foreboding doom builds.

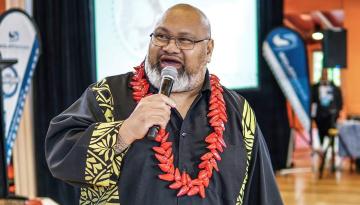

Mammootty in a still from Bramayugam.

Mammootty in a still from Bramayugam.

With a sick smile and a creepy cackle, Kodumon insists that one’s station in society isn’t always defined by where they were born, but can be changed by their ‘karma’. All he wants in exchange for his hospitality, he says, is for Thevan to be his personal iPod, and sing songs for him upon demand. It sounds like a good deal to him. But almost immediately, he learns that the house holds many secrets, the most alarming of which might be connected to the sounds of clamouring and clanging emanating from the attic.

With hat-tips aplenty to the works of Andrei Tarkovsky, Christopher Nolan, Robert Eggers, and most significantly, Gothic horror of the 1940s, Bramayugam is filmed in a mesmerising monochrome that harkens back to the glory days of Nosferatu and Universal monsters. But as old-fashioned as Sadasivan’s inspirations may be, his anxieties feel frighteningly urgent. It is clear almost instantly that the film’s primary theme is caste-conflict. Thevan is initially subservient, even going so far as to scold Kodumon’s cook for speaking ill of their ‘master’ behind his back. This, the movie says, is how the oppressed have been wired to operate. Choice is merely an illusion for people like Thevan, an idea that the movie demonstrates through a game of dice that he obviously loses because it’s been rigged against him.

It doesn’t take him too long to realise that he isn’t going to be allowed to leave the mansion at all, bound as he is by his accursed fate. And this is when, while dealing with his sudden desire to introduce lore, Sadasivan begins building a roadmap to the rude shock that he wants to deliver. Bramayugam isn’t merely a film about oppression, it’s a film about infighting among the oppressed. You’ve been living off scraps all your life, the cook tells Thevan in one scene, foreshadowing the dogfight that he — the son of a ‘housemaid’ — will initiate in the climax. It’s a move straight out of the Bong Joon-ho playbook, and Sadasivan underlines his grand statement in the film’s final moments, when the cook is killed by Portuguese invaders, implying that internal disharmony was the main reason why India fell to the Europeans.

Mammootty in a still from Bramayugam.

Mammootty in a still from Bramayugam.

This is the ‘bramayugam’ — the age of madness. God didn’t create these divisions, the film says; they were created by men. And Bramayugam represents the dominance of men by virtually erasing women from the equation. There’s room only for one female character, a forest-dwelling succubus whose minor presence is more confusing than anything else. She exists, perhaps, only as an Easter egg that those familiar with the folklore would appreciate, and appears in the film’s opening scene, before the spectacular title card, and then once again much later, when Thevan spots her mid-liaison with Kodumon.

Read more – Bhoothakaalam: Stunning Malayalam horror film is an antidote to the toxic Conjuring franchise

Bramayugam is a suitably ambitious (and understandably flawed) follow-up to Sadasivan’s Bhoothakaalam, pound for pound the best Indian horror movie in years. More than anything else, the film’s immersive storytelling and welcome aversion to cheap scare-tactics establishes Sadasivan as the country’s foremost horror filmmaker — he’s India’s answer to Mike Flanagan. Men are doomed to fight endless wars among themselves, while women are literally erased from existence. Evil, greed, and toxicity perseveres. This is the hopeless (and sobering) note that Bramayugam ends on. Madness is only an excuse, the real rot lies within.

Post Credits Scene is a column in which we dissect new releases every week, with particular focus on context, craft, and characters. Because there’s always something to fixate about once the dust has settled.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.